“Like she was there in my living room.” That’s how Officer Dwayne Myers, played by Danny John-Jules in the hit British TV series Death in Paradise, described the delight of listening to a narrator read an audiobook. Officer Myers is not alone in embracing the medium. It’s estimated that more than half of the United States population alone has listened to audiobooks at some point in their lives, including 38% over the past year. And while the books themselves have to be interesting to capture listeners’ attention, the job requires much more than simply reading words off a page. The narrators help make the content sing.

People listen to audiobooks for all kinds of reasons: while driving, to compensate for poor eyesight, to combat insomnia, and more. Matthew Spiegel, a 91-year-old literature student of mine in Fort Lauderdale, has enjoyed audiobooks instead of reading for the past decade.

“The ear does more than the eyes do,” says Spiegel. “The voice emotes. If a narrator is good, the story really comes alive, and that makes all the difference. These people are amazing actors.”

Narrating for audiobooks is a form of voice acting. And while voice actors provide voice-overs for video games, animation, commercials, and other media, audiobook narrators specialize in recording stories for entire books. Besides acting skills, the job requires exceptional breath control, stamina, and reading ability to put across a story effectively.

Narrators learn to match the energy of the narrative—whether reading about a romantic rendezvous or an escaping criminal. That’s because despite the high technology involved in recording, the industry employs an age-old skill: storytelling.

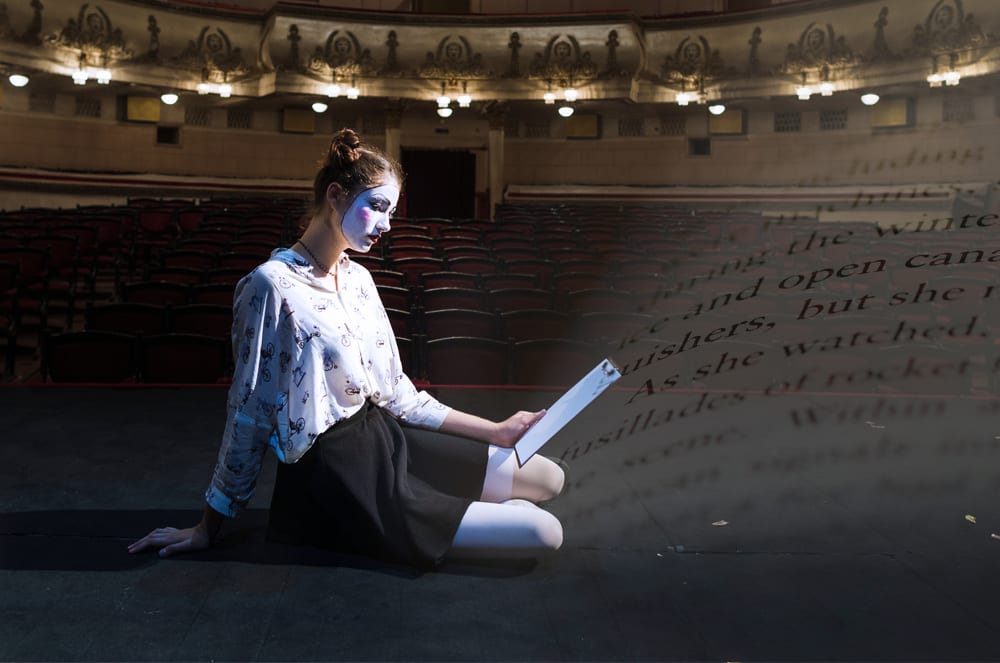

Karen Merritt. Photo courtesy of WAOB® Audio Theatre

Karen Merritt. Photo courtesy of WAOB® Audio Theatre

Essential Storytelling Skills

Whether you engage with an audiobook, a podcast, or even a presentation onstage, you are listening to a story unfold through the speaker’s voice.

“All voice actors, whether they’re narrators or not, need good storytelling skills,” says Karen Merritt, a voice actor in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Vice President Membership of the Elegant Speakers & Listeners (ESL) Toastmasters Club. “They need to identify the audience, grab the listeners’ attention right away, make a connection, and decide upon the perspective of the character.”

To make all this happen, narrators must first and foremost excel at vocal variety. If they read too quickly or don’t articulate well, for example, the story can be hard to follow. To evoke suspense, they might slow their pace. To create intimacy, they can speak closer to the microphone. And while the “heavy lifting” of evoking emotion must come from the text, their own emotional responses to the story inform their readings. For example, a narrator who feels sadness at the death of a character will convey that feeling through their voice.

Additionally, Merritt employs distinct character voices, varying qualities like volume, pitch, tone, rate of speech, and accent to distinguish one from another. She has worked on audiobooks, commercials, video games, and training videos, and often imagines her characters’ physical qualities to help her feel like she “knows” them. And to ensure that each voice is consistent and distinct, she keeps track of them on a spreadsheet.

If you lack a good ear for accents, however, don’t despair. According to the Pathways Level 3 project “Connect with Storytelling,” you don’t need to be an expert at creating characters. You can often give the impression of a different speaker with just a slight variation in tone.

Surprisingly, many voice actors even incorporate body language and facial expressions in their performances. Merritt explains that although listeners don’t see it, the body affects the voice. Try saying hello without smiling and then with smiling, she says, and you will hear the difference. This also works for live storytelling, except in that case, audiences respond to what they see as well—be it a frown, a shrug, or moving to a different spot on the stage.

Storytelling in Toastmasters

Merritt credits Toastmasters for helping improve her storytelling and other voice acting skills. Former Toastmaster Thomas Miller, who specializes in non-fiction narration and is the host of four podcasts, does as well.

As the “Connect with Storytelling” project notes, “Stories have been spoken aloud and passed down from generation to generation in every civilization around the world.” It should come as no surprise then that the elective project appears in each of the six paths in the Pathways learning experience. This project teaches speakers how to apply storytelling techniques and descriptive skills to their presentations.

“Toastmasters improved my skills in every way,” says Miller. “Including confidence.” If narrators don’t project confidence in their voices, they have a hard time engaging the audience. In addition, says Miller, Toastmasters helped him sound natural.

“All voice actors, whether they’re narrators or not, need good storytelling skills.”

—Karen Merritt“A good audiobook narrator mustn’t sound like they’re reading,” notes Miller, the former Club President of the Cloud Nine Toastmasters club in Aspen, Colorado, and TNT Toastmasters Club in Addison, Texas. “Instead, like any good actor, they must embody the material. What’s more, I always have an image of a person I know when I’m narrating, and I’m reading the book to them. In other words, tell your audience a story, don’t simply deliver it.”

Toastmasters also helped Miller understand and adjust to the needs of his audience. Unlike with public speaking, he explains, people often listen to audiobooks through headphones or earbuds. Mastering that special environment is a big part of the job. That includes learning how to control “mouth noises” like clicks and pops, which he calls “the audiobook narrator’s nemesis.” Even live speakers must learn to rein in habits like lip-smacking.

“Public speaking is for a room or an auditorium,” says Miller. “But audiobooks often go directly into the ear. They are more of a ‘pillow-talk’ kind of medium. That means the inflections have to be softer, perhaps even a little more deliberate. Getting into someone’s head is an intimate experience. It’s a sacred space.”

Strategies to Become a Strong Storyteller

Breaking into any new field can be a challenge, but it’s often worth the effort. To become a strong storyteller, try these strategies.

- Purchase or check out audiobooks from the library to study them for pacing, breath control, intonation, and other characteristics. You can also listen to podcasts, voice-overs, and other storytellers to learn what speaking skills the narrators use. (And don’t forget those Toastmasters meetings!)

- Record yourself reading a book aloud. You may decide to invest in a good microphone or other equipment at this stage. Then, analyze your performance to determine what you do well and how you can improve. Your Toastmasters mentor or fellow club members can also provide feedback.

- Consider taking a class or volunteering for podcasts or other projects until you feel confident. Speakers can also volunteer at local service organizations, libraries, and other venues to gain experience telling stories to a live audience.

- If you are interested in becoming a voice actor professionally, think about recording your performances to create a demo for prospective clients. Then get ready to promote yourself. Search career websites for casting calls as well as seeking out opportunities to freelance.

Merritt was already an actor, director, teaching artist, and mother before recording audiobooks. Prior to transitioning into the industry, she took the ACX Master Class to develop her skills. (ACX is a platform for narrators, authors, and publishers to connect to produce audiobooks.)

“This class sparked a major shift in my career, as I learned how to not only narrate, but also produce audiobooks from home, working around my sons’ schedules,” she says. “It was a lot of work, but I love it!”

Miller, meanwhile, majored in broadcasting and worked as a local news anchor while still in college. He parlayed that experience into owning his own broadcast production business. When audiobooks became available to stream on smartphones, he attended a three-day event facilitated by leaders in the field. That, in conjunction with his professional background and experience in Toastmasters, was all he needed to launch his new career.

“The most important thing I learned,” he says, “is that whatever I did, I needed to be Thomas Miller. I needed to develop my own style.”

While Miller’s approach is intimate and straightforward, yours may be particularly lively or even a little eccentric. That’s because in all forms of storytelling, you are always ultimately yourself. The characters are in your listeners’ heads.

Of course, there are many ways, and venues, in which to tell a story. Try to experiment with a number of them until you find your comfort zone. Once you become a confident storyteller, you’ll fit into anyone’s auditorium, car, or living room.

Caren S. Neile, PhD teaches, writes, and stockpiles social capital in Boca Raton, Florida. Visit her at carenneile.com

Related Articles

Storytelling

Bring Your Speech to Life With a Story

Storytelling

Previous

Previous

Previous Article

Previous Article