I’ll never forget the first time I took a job as a conference keynoter. I came prepared with an outline to help me recall the main ideas of my 45-minute speech. Then, just before I walked onstage, my hosts told me they couldn’t find the lectern, where I had planned on placing my notes.

It was one of those times a speaker dreams about. And then wakes up screaming.

Let’s be clear: There is no shame in using notes for a speech. Those journalists and politicians you see on the news usually read their lines from a teleprompter. But wouldn’t it be nice to be able to move around the stage a little, make great eye contact, and not have to worry about losing your notes, your place—or your lectern?

Knowing It Cold

For keynote speaker and speaking coach Sabina Nawaz, the ultimate prevention to a recurrence of my nightmare is not just memorization, but “memorization on steroids.”

“I’ve found one approach to public speaking works best,” she writes in the Harvard Business Review. “Knowing your ‘script’ cold.” This means not only intense rehearsal, but the right kind of rehearsal.

According to Nawaz, “Most people start at the beginning each time they practice, resulting in an unevenly memorized script; the introduction is solid, but the conclusion is shaky.”

This used to happen to John Gentithes, President of the West Boca Toastmasters Club in Florida.

“I would often begin very strong and end weak,” he says, “because I practiced from the beginning and then whenever I made a mistake [in practice], I started over. So I practiced the beginning really well, but not as much the end.”

Instead of learning your script in sequence, Nawaz advises, start rehearsing each time at a random section and take it from there. Then sew the whole thing together with good segues.

Knowing a script or presentation cold, she says, also means taking the time to craft the words and sequence of what you plan to say, and then rehearsing them over and over.

In this way, she says, you’ll be less nervous and can effortlessly move from point to point. You are free to be fully present, and thus more responsive to your audience.

That’s especially true when you speak extemporaneously.

Memorization vs. Extemporaneous Speaking

Extemporaneous speaking is not Table Topics®. It means preparing what you are going to say well in advance, while exactly how you say it may be different each time you speak. It can be more comfortable for speakers than memorization because it requires mastery of the material, not of the exact wording.

It also allows for the flexibility to subtly adjust a speech to each unique audience and situation. So it can be easier to deliver an effective presentation no matter whom, or what, you face.

As a new speaker 20 years ago, Gentithes routinely memorized his speeches. He did notice that they sounded a bit canned, and his gestures and eye contact suffered. But he felt constrained by notes, and he wasn’t yet ready to think on his feet.

“Strategize how to handle a memory lapse as part of your preparation. Craft two or three phrases you can use.”

—Sabina NawazMore than once, however, Gentithes realized that while he was onstage, distractions like the ring of a cellphone or the sound of a sneeze rattled him, causing him to lose his place in his memorized script. Then, not long into his Toastmasters career, he was speaking at an Area speech contest when he heard a loud explosion off in the distance.

“It might have thrown me for 20 seconds,” he says, “but it felt like 30 minutes. I never did regain my bearings.”

Since then, Gentithes, like Nawaz, organizes his speeches into bite-sized units that are easier to remember, and that he can rehearse bit by bit. So if he gets thrown off, he can more easily find his way back.

He rarely if ever memorizes. Relating these units extemporaneously rather than by rote not only helps him remember, but it also makes movement easier to master. And movement, says Nawaz, helps commit more words to memory.

“If you’re going to deliver your talk standing up, don’t sit down to rehearse,” she warns. “I will often mark a mini stage and walk across it as I would during the actual speech. Associating a section of the speech with a place onstage is a memory aid.”

A No to Memorization

Faye Andrusiak, DTM, is Vice President Public Relations and the Club Secretary of Treasure Chest Club in Yorkton, Saskatchewan, Canada. After being a Toastmaster for almost 30 years, she now rarely memorizes her speeches.

“I am a nervous speaker,” she says, “and if I forget my speech, I can’t get back on track. Over the years I’ve found that simply learning my speech is more effective. I am much more confident at the lectern.”

When Andrusiak uses notes, she writes down only key phrases or statistical information. “However,” she says, “notes can be a hindrance as well.” She finds PowerPoint slides helpful. When the equipment is in good working order and people know how to use it, PowerPoint can be a boon to speakers, although it, too, can disrupt eye contact and movement.

In general, if you do use PowerPoint, try to use as few words as possible per slide. And remember, PowerPoint is not a replacement for knowing your speech; it’s a visual supplement.

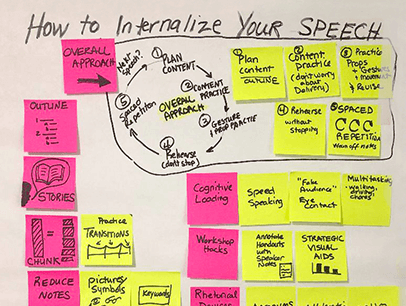

Here are some more memory tools to help with speeches:

Mnemonic devices.

Find a learning technique to help improve your memory. This is how I quickly saved myself in the keynote debacle mentioned in the beginning. In the few minutes I had to learn my notes, I used alphabetization and acronyms (music students will remember “Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge” for the notes on the scale) to highlight the most important points.Storytelling.

Telling a story helps you (and your audience) remember your content better. There is a long, strong connection between narrative and memory for numerous reasons, including simple brain physiology. In addition, stories flow downhill. That is to say, it’s relatively easy to remember their sequence because they are, by and large, logical. You can’t walk out of a store with an item until you’ve paid for it. And if you do, that’s memorable!Keep it loose.

Perhaps the most important thing about remembering speeches is that by and large, your audience doesn’t know what you’re going to say. If you begin by stating that you have three points to make, and you forget one, you may be able to come up with another. But the more specific you are in your introduction, the more you are tied to what you planned to say. And that can backfire when you’re nervous and forgetful.When All Else Fails

Even the best-laid plans of well-prepared speakers can go awry. That’s why Nawaz recommends having a backup plan for forgetfulness.

“Strategize how to handle a memory lapse as part of your preparation,” she urges. “Craft two or three phrases you can use. Knowing that I have these go-to phrases makes me less nervous about forgetting.”

Such phrases include: “Let me refer to my notes,” or “I’m struggling to remember my next point. Let me take a moment and step back.” Or even just take a sip of water. Your audience will appreciate your moment of vulnerability.

Then there are the times that you remember something you should have said earlier. Here’s your chance to recoup your memory lapse. “What I haven’t told you is …” has saved me on more than one occasion.

I didn’t use that statement when the lectern disappeared, however. I didn’t need to. That’s because the audience never knew that anything was wrong.

Caren S. Neile, PhD teaches, writes, and stockpiles social capital in Boca Raton, Florida. Visit her at carenneile.com

Previous

Previous

Previous Article

Previous Article