Common wisdom tells us that storytelling is the most effective way to get audiences to remember our messages—that telling tales is a surefire way to make an indelible mark on listeners’ minds and get them to respond to our calls to action. But a cognitive neuroscientist who has made a career of studying what people remember from speeches says memory is far more complex. Influencing audience recall requires a deeper understanding of how memories are formed and how they influence decisions.

Being memorable, it turns out, is about more than just having a good story.

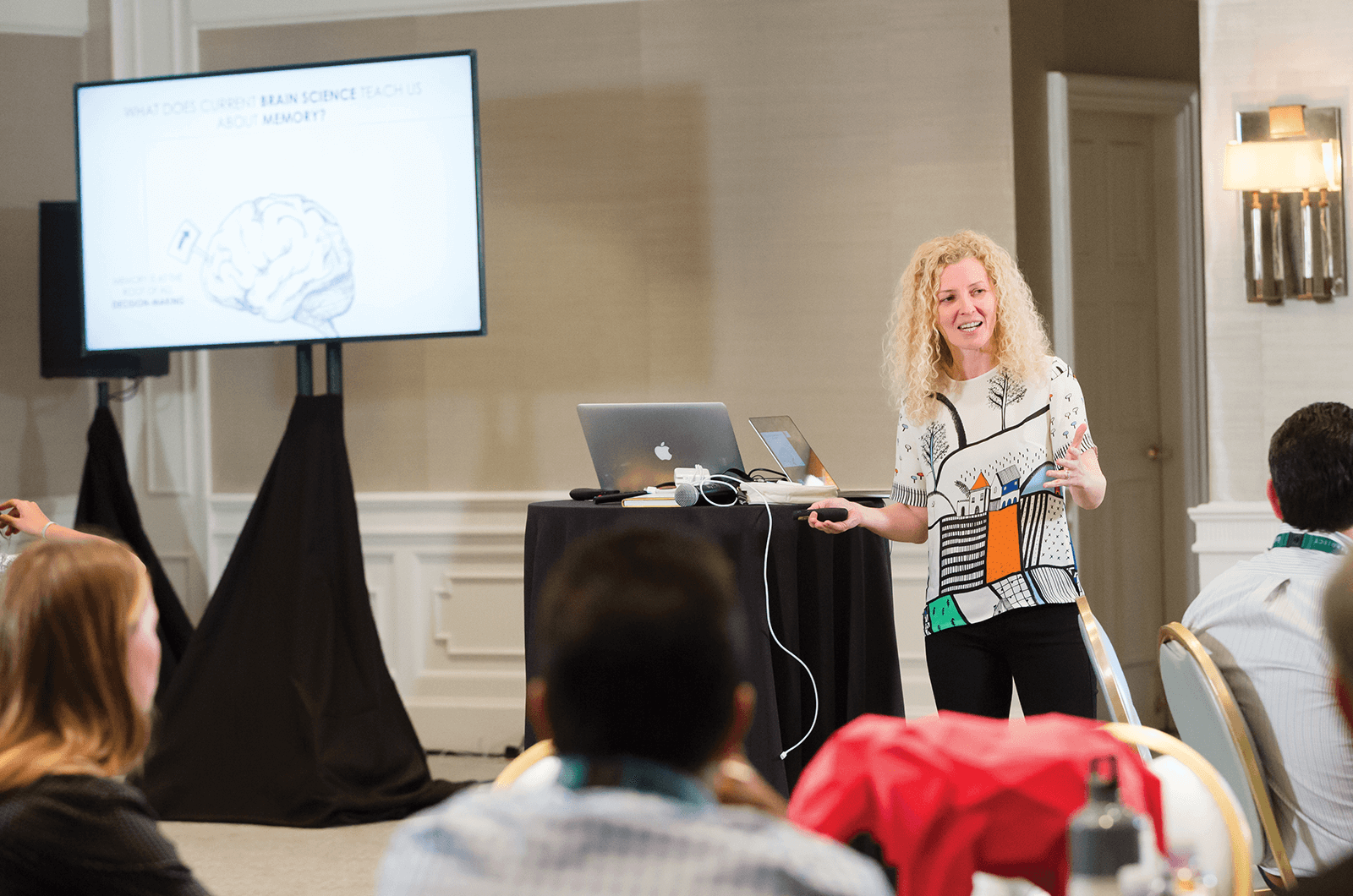

Carmen Simon, Ph.D., is the founder of Memzy, a company based in San Francisco, California, that uses neuroscience and cognitive psychology to help organizations create memorable messages. She holds doctorates in cognitive psychology and instructional technology and authored the book Impossible to Ignore: Creating Memorable Content to Influence Decisions. Simon’s science-based approach to improving what audiences remember from presentations has been applied by the likes of Scott Adams, creator of the popular American cartoon Dilbert, who used the techniques in developing an online presentation to help promote his book How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big. Adams’ presentation was honored by the online site SlideShare as one of the best of 2014, topping a multitude of contenders for the honor.

Simon’s research into presentations began as she studied scores of speeches and found much of the content to be forgettable, even when accompanied by well-designed slides. In one of her most well-known studies Simon asked 1,500 research participants to view a 20-slide presentation with one core message and then followed up two days later to ask what they recalled from the presentation. People remembered only four of the slides on average, a confirmation that presenters need to approach content design and message delivery in innovative ways to make them more memorable.

What Makes a Presentation Memorable?

Simon says speakers can use techniques to improve the odds of audiences remembering—and more importantly, later acting on—their key messages. Here are a few of those tactics.

Making Your Presentation Memorable

The end game for any speech is moving audiences to action, and that’s only possible if your take-away messages linger in audiences’ memories. Yet memory is more complex than we think it is. For example, if you were asked whether red or green was at the top of the traffic light, could you answer with certainty? Could you recall the design on the back of a penny?

Carmen Simon, co-founder of Rexi Media, a San Francisco-based presentation skills consulting firm, conducted a study on how many slides people actually remember from a typical PowerPoint presentation. About 1,500 participants were invited to view a short, online PowerPoint presentation of 20 slides, each containing only one core message.

After 48 hours, people were asked to recall anything they could remember about the presentation. The results were sobering, Simon says. Participants remembered on average only four slides out of 20. But on the flip side, significant changes to every fifth slide aided recall, she says.

What lessons can be drawn from the study? Simon says a number of techniques can help boost audience recall of your messages.

People remember the unusual. “For the brain to remember, presenters must deviate from a pattern in some significant way,” Simon says. If everything in your slides is equally intense (graphics, color, large font size) or equally neutral or bland, that sameness acts as an audience sedative, she says. But when a slide’s look or content varies from what an audience expects, focus and recall increases—as evidenced by the improvement in memory shown in the study by significantly altering every fifth slide.

Self-generated content improves memory. Audiences remember messages longer when asked to participate in or “co-create” your speech in some way. That could be as simple as leaving word blanks on your slides for audiences to verbally fill in, Simon says, or other participatory techniques. “Because most of us do so much research for our presentations, we think we have to pack every last thing we’ve discovered into an hour-long presentation, versus leaving some space for audiences to participate,” says Simon. “Participating gives people a stronger sense of ownership in the process, which creates a stronger hook in their memories.”

Go beyond aesthetics to meaning. While good PowerPoint slide design is important, speakers get into trouble when they worry too much about the aesthetics of their slides rather than the meaning they impart. When you invite audiences to process information deeply by invoking senses and provoking thought, they recall more. “You could contact audience members two or three days after your presentation, and they might not remember much of your slide content,” Simon says. “But they’re very likely to remember how you made them feel during the presentation.”

— Dave Zielinski (from the July 2014 article "Add Story to Your Slides")

Give them something they anticipate ... and then surprise them.

Simon’s research shows speakers should use a combination of recognition and surprise to embed themselves in audience memory. One of the best ways to capture attention is to break a pattern after audiences’ brains become “habituated.” People begin to disengage from presentations when messages or slides become too predictable.

Instead, the neuroscientist suggests breaking patterns by alternating between slides that are visually intense and slides that are visually simple, for example, or moving from a routine of seriousness to something funny.

Create the right blend of the ‘Big 3’ elements.

When Simon studied what made some stories more memorable than others, she found the best had the proper mix of three components: perceptive, cognitive and affective. Perceptive includes sensory impressions made in context and actions described over a timeline. Cognitive refers to facts, meaning or abstract concepts. Affective includes the elements of emotion.

A combination of the three components proves memorable because it activates more parts of the brain as opposed to a message filled primarily with facts and abstract concepts, which activates only language processing and comprehension areas.

Simon points out that many speakers struggle in the affective area because they think their content is too dry or technical to engage audiences on an emotional level. “But emotion doesn’t just come from the nature of your content,” she explains. “If you think your content is not intrinsically compelling, you as the speaker have to become the source of emotion.”

Simon offers the example of two engineers she watched present on the benefits of predictive analytics software. “They were so excited and passionate about the topic that I built lasting memory traces just from their emotion, even though I had no natural interest in the topic,” she says.

“If you think your content is not intrinsically compelling, you as the speaker have to become the source of emotion.”

—Carmen SimonDon’t shy away from repetition.

One of the most overlooked tactics for boosting audience memory is simple repetition. Simon views many presentations each month and is usually surprised at how infrequently content is repeated. This is because speakers fear appearing too premeditated in their approach or feel they need new information for the novelty of it, Simon observes.

On the other hand, songs that top the pop charts constantly revisit the same phrase. For example, one study by Joseph Nunes of the University of Southern California found that hit songs repeat lyrics up to 20 percent more than songs ranking lower on the charts. While you don’t want to go overboard with repetition, you also don’t want to avoid it.

Be ‘future focused’ with memory techniques.

Many problems connected to audience recall are “not about forgetting the past but rather forgetting the future,” Simon explains. While speakers may have what they consider a strong message at Point A (during the speech), if the audience doesn’t remember or act on it later at Point B (when they’re facing a buying decision or other important choice), the speaker’s mission has failed.

While retrospective memory, or remembering the past, is useful, Simon says it is prospective memory—remembering to act on a future intention—that “keeps people in business” and makes speakers’ messages more influential in audiences’ future decisions.

Speakers need to build in audiences’ minds stronger associations or “cues” between the content shared at Point A and actions they later take at Point B. For example, before making a sales presentation on analytics software, a presenter could think about something potential clients might use daily. It could be a tool like Salesforce, for example. Then the presenter might ask, “How can I associate concepts I want prospects to remember about my product with Salesforce?” One solution would be to associate features of the analytics software with functions of Salesforce that the prospect uses on a regular basis.

The presenter would then repeat the association throughout the sales pitch. As Simon advises on her blog, “You prime your prospect’s brain to remember what is important and, with enough repetition and the promise of a strong reward (e.g., ‘sell more when you use this’), they will think of you each time they visit that particular functionality in Salesforce.”

Understanding how and why our brains retain content is key to making our own speeches stand out from the crowd. By creating stronger associations between our presentation content and subsequent triggers, we make our message more memorable and actionable.

For more ideas and techniques, you can view other top SlideShare presentations or key digital trends in presentations for 2018.

Dave Zielinski is a freelance writer in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and a frequent contributor to the Toastmaster magazine.

Previous

Previous

LEADERSHIP SKILLS: 5 STRATEGIES TO LEAD A TEAM THROUGH CONFLICT

LEADERSHIP SKILLS: 5 STRATEGIES TO LEAD A TEAM THROUGH CONFLICT

Previous Article

Previous Article